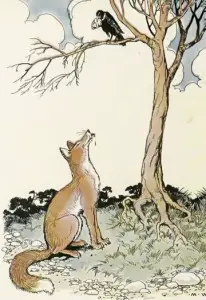

The Fox and the Crow (from the Fables of Aesop)

Փառասէր մարդն երբոր գովուի,

Շուտով կը հաւատայ ամէն խօսքի։

Ագռաւը բերանն

Առակս օրինակ է ունայնասիրութեան, որ անանկ կը կուրացնէ մարդուս միտքն, որ սուտ գովասանքով խաբուի կը հպարտանայ, մինչեւ ամենքը վրան կը խնդան։

A Crow having taken a piece of cheese out of a cottage window, flew up into a high tree with it, in order to eat it; which a Fox observing, came and sat underneath, and began to compliment the Crow upon the subject of her beauty. 'I protest,' says he, 'I never observed it before, but your feathers are of a more delicate white than any that ever I saw in my life! Ah; what a fine shape and graceful turn of body is there! And I make no question but you have a tolerable voice. If it is but as fine as your complexion, I do not know a bird that can pretend to stand in competition with you.' The Crow, tickled with this very civil language, nestled and riggled about, and hardly knew where she was; but thinking the Fox a little dubious as to the particular of her voice, and having a mind to set him right in that matter, began to sing, and in the same instant let the cheese drop out of her mouth. This being what the Fox wanted, he chopped it up in a moment, and trotted away, laughing to himself at the easy credulity of the Crow.

They that love flattery (as it is to be feared too many do) are in a fair way to repent of their foible in the long run. And yet how few are there among the whole race of mankind who may be said to be full proof against its attacks! The gross way by which it is managed by some silly practitioners, is enough to alarm the dullest apprehension, and make it to value itself upon the quickness of its insight into the little plots of this nature: but let the ambuscade be disposed with due judgment, and it will scarce fail of seizing the most guarded heart. How many are tickled to the last degree with the pleasure of flattery, even while they are applauded for their honest detestation of it! There is no way to baffle the force of this engine but by every one's examining, impartially for himself, the true estimate of his own qualities: if he deals sincerely in the matter, nobody can tell so well as himself what degree of esteem ought to attend any of his actions, and therefore he should be entirely easy as to the opinion men are like to have of them in the world. If they attribute more to him than is his due, they are either designing or mistaken: if they allow him less, they are envious, or, possibly, still mistaken; and, in either case, are to be despised or disregarded. For he that flatters, without designing to take advantage of it, is a fool; and whoever encourages that flattery which he has sense enough to see through, is a vain coxcomb.

Comments

Post a Comment